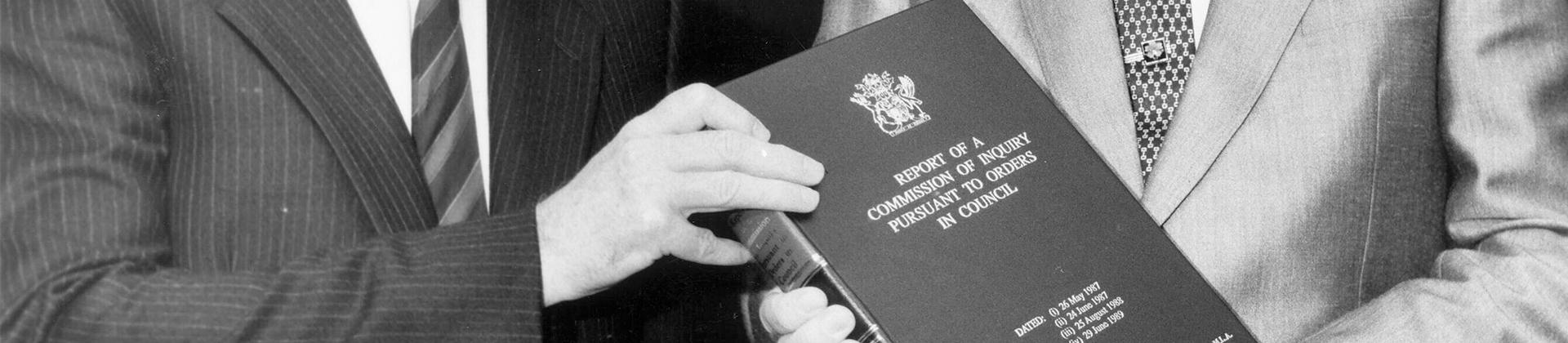

"The Commission’s expenditure of $17 million for the year represents a significant investment by the State of Queensland. … This represents some of the cost of repairing the damage done to the body politic by the evils identified by the Fitzgerald Commission of Inquiry … and of measures to prevent the recurrence of such damage …”

---Sir Max Bingham, Chairman

Much was demanded of the Commission during its establishment phase. While seeking to establish its own functions and processes, it also performed the continuing tasks of the Fitzgerald Commission of Inquiry, and assumed a backlog of work from the Police Internal Investigations Section and the Police Complaints Tribunal. The Queensland Police Service was undergoing dramatic change, particularly in relation to selection, promotion and training of its officers, and a high level of assistance was required from the CJC for the reform process. The Commission was also providing assistance to the Office of the Special Prosecutor. Staff with the necessary specialised skills were in short supply, particularly within Queensland, making recruitment to and establishment of the CJC prolonged and difficult.

In December 1990, the Commission moved from its offices in Ann Street Brisbane to its new home on Coronation Drive at Toowong.

A commitment to accountability

The CJC was created as a consequence of a public inquiry showing that public institutions were neither accountable nor effective. With that heritage, the Commission was sensitive from the outset to the need to be publicly accountable while maintaining appropriate confidentiality over its investigations, intelligence collection and analysis.

The CJC therefore took steps to enhance its own accountability, including:

- Having the Chairman, Commissioners and all Commission staff complete declarations of personal particulars and private interests and associations

- Ensuring that its work was seen in the public arena by conducting public hearings

- Educating the public on criminal justice issues via open hearings and public reports

- Addressing a diversity of public groups, as well as interacting with the media, the public, and responding to complainants.

The development of CJC functions

The Official Misconduct Division (OMD) included a Complaints Section and Multi-Disciplinary Teams. While the Complaint Section’s role was to receive all complaints or information concerning misconduct or official misconduct, the function of the Multi-Disciplinary Teams was to investigate the more complex complaints and proactive matters of major or organised crime. An infrastructure of procedures, systems, methods and training had to be put in place even while the OMD undertook some 50 investigations into matters as diverse as the bribery of public officials and large-scale narcotics trafficking.

By 30 June 1991, the CJC had received 2453 complaints containing 5504 allegations, with nearly 74 per cent of these coming from members of the public. Prisoners and detainees accounted for 6 per cent and were the next most significant group of complainants.

Of the allegations received, 78 per cent were about the Queensland Police Service.

Public inquiries

In 1990-91 the CJC held three public inquiries and commenced a fourth:

- The Jury Tampering Inquiry arising out of the trials of Brian Austin and George Herscu

- The Corrective Services Commission Inquiry arising out of allegations of the involvement of prison officers in prostitution and drug trafficking

- The Huey Diaries Inquiry arising out of the use by Channel 7 of extracts from the diaries of former Superintendent John Huey and their apparent misappropriation from the property office of the QPS

- An inquiry concerning payments made to Aldermanic candidates and Councillors of the Gold Coast City Council.

Corruption prevention

One of the functions of the OMD was to assist and advise law enforcement and public sector agencies, companies and institutions, auditors and others about detection and prevention of official misconduct. The concept of corruption prevention was based on the principle that prevention is better than cure and on the premise that corruption prevention was a managerial function. Some of the managerial weaknesses the CJC identified as conducive to corruption included the lack of or poor policies, unenforceable legislation, inadequate instructions, excessive discretion and lack of effective supervision.

Proceeds of crime

By the late 1980s it was generally agreed by law enforcement throughout the world that seizing the assets and money of criminals was an extremely effective weapon in the fight against crime. By 1989, all Australian states had legislation that enabled them to confiscate the proceeds of criminal activity. In Queensland, this was the Crimes (Confiscation of Profits) Act 1989. By June 1991 the CJC’s Criminal Assets Section had been responsible for freezing $430,000 in assets, with a further $410,000 expected to be restrained within months.

Research

The CJC Research Division made a conscious effort to see that all of its research had practical implications. As recommended by Fitzgerald, the CJC consulted with various segments of the Queensland community, often by seeking submissions on particular issues.

The CJC reports published during 1990-91 included the jury system and criminal trials in Queensland, report of an investigative hearing into alleged jury interference, double jeopardy, atittudes toward the Queensland Police Service, and monitoring and reviewing the CJC.

For more information on the CJC’s work in 1990 - 1991, you can read the full Annual Report 1990 - 1991.