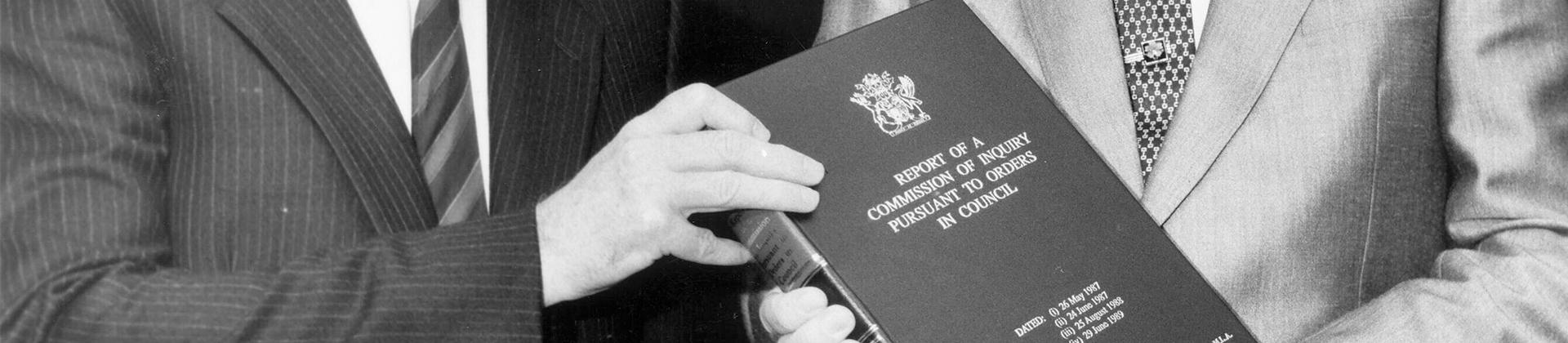

The CJC arose out of the Fitzgerald Inquiry, which had been set up in response to media revelations on crime and corruption in Queensland.

The Fitzgerald Inquiry investigated the policing of organised prostitution, unlawful gambling, sale of illegal drugs, and associated misconduct by members of the Queensland Police Force.

The Fitzgerald Report recommended the creation of a new entity to be known as the Criminal Justice Commission. It was to be permanently charged with the monitoring, reviewing, co-ordinating and initiating reform of the administration of criminal justice. It was also to fulfil those criminal justice functions not appropriately carried out by the police or other agencies.

From the outset, the CJC was a complex organisation with multiple roles, functions and responsibilities. There was no other model for an organisation of this type anywhere else in Australia.

Even today, Queensland remains the only state in Australia to unite the investigation of organised crime, police and public sector oversight, and witness protection within one agency.

With an initial budget of $5 million, the CJC laid the foundations for many of the structures, powers and operations that carry over to the present Crime and Corruption Commission.

About the CJC

"It is a matter of great pleasure to be able to record the quality, enthusiasm and idealism of the team which the Commission has been able to put together. They are mostly young Queenslanders who are dedicated to the carrying out of the reforms recommended by the Fitzgerald Report …” Sir Max Bingham, first Chairman of the CJC.

The CJC came into effect with the Criminal Justice Act 1989 (31 October 1989). The first Chairman was appointed on 21 December 1989.

For the period November 1989 to April 1990 the CJC undertook operations on a limited basis, as only part of the Criminal Justice Act had been proclaimed. The remainder of the Criminal Justice Act came into effect from 22 April 1990.

The purpose of the CJC was “the reformation of the administration of Criminal Justice in Queensland and the fulfilling of those criminal justice functions not appropriately carried out by the police or other agencies”.

Its aims and objectives were:

- enhancing public, parliamentary and forensic awareness of the problems which beset the administration of criminal justice in Queensland

- exposing corruption and official misconduct through hearings and reports to Parliament

- providing evidence which leads to the prosecution of persons engaged in corruption or official misconduct, either before the courts, the Misconduct Tribunals or by disciplinary proceedings

- reducing the incidence of misconduct, official misconduct and corruption in the police service and other units of public administration

- upgrading the ability of the police service to tackle major and organised crime

- providing comprehensive and accurate intelligence briefings to law enforcement agencies, Parliament and the community on the state of major and organised crime in Queensland.

Governance structure

The CJC was headed up by a five-member group referred to as the Commission — a Chairman and four other members appointed by the Governor-in-Council on the recommendation of the Minister, who was at that time the Premier of Queensland.

First Chairman

The CJC’s first Chairman was Sir Max Bingham, a distinguished Tasmanian lawyer and Rhodes Scholar.

Before coming to the CJC he had held numerous public offices in Tasmania, including Crown Prosecutor and Police Magistrate. His long career as a State Parliamentarian in Tasmania, from 1969 to 1984, included terms as a Police Minister, Opposition Leader, Deputy Premier, Attorney-General and several other ministerial portfolios. He was a foundation member of the National Crime Authority from 1984 until 1987.

First Commissioners

Sir Max Bingham was joined by Mr Jim Barbeler, Dr Janet Irwin, Mr John Kelly and Professor John Western to form the first five-person Commission of the CJC.

Parliamentary Criminal Justice Committee

Although an autonomous and independent body, the CJC was made accountable to Parliament, the community and the courts by the Criminal Justice Act.

One of the accountability mechanisms for the CJC was the establishment of the Parliamentary Criminal Justice Committee. Its first Members included:

- Mr Peter Beattie, Member for Brisbane Central (Chairman)

- Mr Mike Ahern, Member for Landsborough, (Deputy Chairman)

- Mr Bill Gunn, Member for Sommerset, (Deputy Chairman from 10 May 1990)

- Mrs Wendy Edmond, Member for Mount Cootha

- Mr N. Harper, Member for Auburn (from 10 May 1990)

- Mr Santo Santoro, Member for Merthyr

- Mr Robert Schwarten, Member for Rockhampton North

- Mrs Margaret Woodgate, Member for Pine Rivers.

Organisational structure

The CJC established a range of internal units to conduct its work:

- Official Misconduct Division – organised crime, police corruption and government corruption teams

- Misconduct Tribunals

- Witness Protection Division

- Research and Co-ordination Division

- Intelligence Division

- Corporate Services Division.

The CJC also housed the function of a Commissioner for Police Service Reviews which operated independently of the CJC. This function was designed to allow any police officer to seek review of a decision relating to an appointment or promotion, transfer, or action for a breach of discipline.

Powers of the CJC

From the outset, the CJC had unique powers to investigate suspected police misconduct and official misconduct in the public sector.

This included the power to:

- require a person to furnish a statement of information to the Commission

- compel the production of records and things relevant to an investigation

- summons people to attend the Commission and give evidence

- conduct hearings at which witnesses may be compelled to give evidence on oath and produce documents

Information obtained under compulsion could not be used against the person in any civil or criminal proceedings.

Key statistics from 1989 - 1990

An analysis of complaint statistics from 22 April to 30 June 1990 shows:

- 66 matters were inherited from the Police Complaints Tribunal, many of which were complicated and of several years standing

- an average of 9 complaints were received per day

- 165 matters referred to the Complaints Section investigators

- 6 matters referred to the multi-disciplinary teams for further investigation

- 27 minor matters referred to the Commissioner of Police

- 80% of all complaints received in this period related to police

- 6 matters were dismissed as frivolous or vexatious

- 333 matters were under consideration.

Reports tabled in Parliament in 1989 - 1990

Two reports were compiled by the Research and Co-ordination Division in relation to the State’s legal and criminal justice systems

- Reforms in laws relating to homosexuality: an information paper and

- Report on gaming machines concerns and regulations

To find out more about the establishment of the CJC, you can read the full CJC Annual Report- 1989 - 1990.