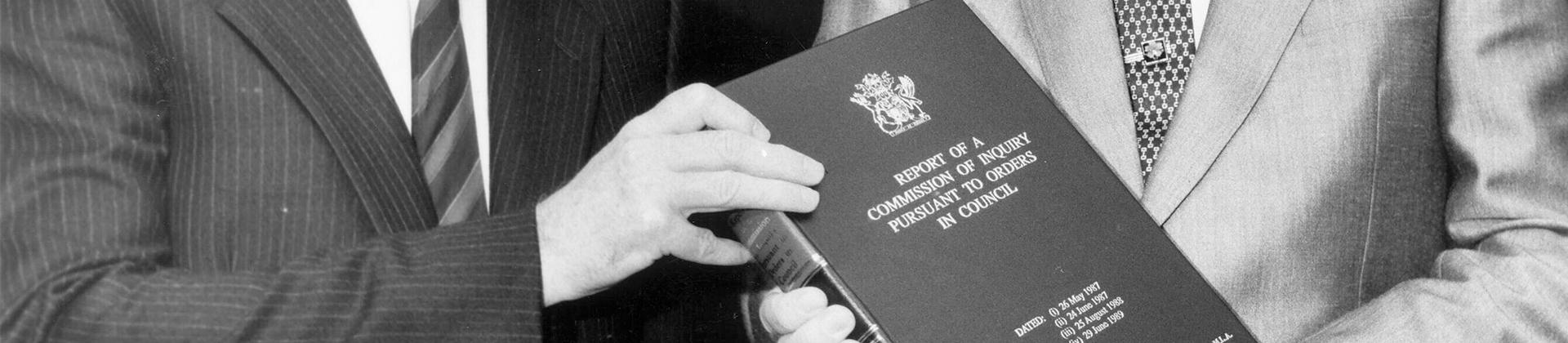

“Systemic corruption does not happen overnight; it builds up over a period of years. Even misconduct which may seem apparently insignificant can, if left unchecked, lead to a major decline in the level of public sector integrity.”

---Chairperson Robert Needham

In addition to its ongoing work in preventing and dealing with official misconduct relating to Queensland public sector agencies, in 2006-07 the CMC embarked on a new national initiative to prevent misconduct.

In March 2006, three state-based integrity bodies (the Independent Commission Against Corruption in NSW, Queensland’s Crime and Misconduct Commission, and Western Australia’s Corruption and Crime Commission) agreed to work together to host the first Australian Public Sector Anti-Corruption Conference (APSACC) in October 2007 in Sydney.

The conference was designed to enable information exchange between corruption prevention management, policy and operational staff nationally and internationally. The inaugural program addressed key jurisdictional areas such as the public sector, local government, police and universities, and issues such as regulation/ licensing, conflicts of interest, public–private interface and whistleblowing.

APSACC continues to be Australia’s premier conference for anti-corruption and integrity practitioners.

Highlights of the CMC’s work during 2006-07 included:

- Finalising 18 organised crime and criminal paedophilia investigations; 17 operations resulted in arrests, charges or restraints

- Commencing 16 paedophilia investigations, 14 in relation to internet offenders and 2 concerning networked offenders, resulting in the arrests of 16 offenders on 40 charges

- Assessing 3,565 corruption matters

- Finalising 107 misconduct investigations

- Holding investigative hearings over 81 days between 1 July 2006 and 30 June 2007, to which 67 witnesses were called. These hearings were held in connection with 13 major crime investigations, including unsolved murders, rape, fraud, drug trafficking, dealing in stolen goods, and suspected terrorist activity

- Seeking and receiving submissions concerning the implementation of recommendations in the Seeking justice report

- Restraining $11.74 million and confiscating $4 million in property from crime figures in Queensland, exceeding its target of $8 million for the year and

- Maintaining a 100 per cent success rate in keeping witnesses safe.

Implementation of the Project Verity model

The implementation of the Project Verity model represented one of the most significant shifts in the Queensland Police Service’s integrity regime since the Fitzgerald Inquiry.

Working closely with the QPS Ethical Standards Command, Project Verity recognised the importance of local line managers in promoting positive behaviour and strengthening the culture of integrity.

The first part of Project Verity would see responsibility for dealing with complaints devolved to the appropriate local level. The second part aimed to improve the speed and efficiency of the disciplinary process.

This was supported by a framework incorporating the monitoring roles of the QPS and the CMC, and a consensual short-form disciplinary hearing process for a trial in a specified QPS region.

Project Verity would be trialled in that QPS region for six months commencing in July 2007.

Police officer jailed on perjury and assault charges

A former police constable, Justin Anthony Burkett, was jailed in August 2007 for attempting to cover up an assault on a woman in a watch-house cell.

He was sentenced to three years imprisonment after pleading guilty to four perjury charges, two charges of attempting to pervert the course of justice, and one count of assault causing bodily harm. Judge Ian Dearden ordered that the sentence be suspended after Burkett had served nine months.

The CMC investigated the actions of Burkett and other police officers in relation to their arrest of a woman in April 2004 for shoplifting and a traffic offence. It was alleged that Burkett hit the woman several times while she was in a holding cell at Loganholme police station. Burkett charged the woman with assault, claiming that she had initially kicked him.

Burkett later gave false testimony during the summary trial of the woman for assault. He had asked two other police officers, via email, to supply false statements, for the purposes of the summary trial. The CMC held closed investigative hearings as part of its investigation. Burkett also provided false information on oath at those hearings.

It is considered a very serious offence for a police officer to provide false testimony on oath, whether to a court or to an investigative hearing.

Jailing of former minister Merri Rose

The CMC investigated allegations that, on 30 October 2006, former minister Merri Rose threatened to smear the reputation of a nominated individual unless the Queensland Premier provided her with a highly paid position in the public sector. The investigation resulted in her being sentenced in the District Court on 31 May 2007 to a term of imprisonment of 18 months, to be suspended after three months.

The CMC Chairperson publicly commented that the jailing of a former minister for the offence of demanding a benefit with threats served as a strong warning that people who sought to corrupt public servants did so at their peril. He also emphasised the value of early reporting of extortion threats.

Fraudulent road safety certificates

On 4 May 2007, Edward Cornelius Moran, a former Queensland Transport inspector, was sentenced to seven years imprisonment for fraud and official corruption offences. Between September 2002 and July 2003, Mr Moran and four accomplices had been responsible for the fraudulent issue of approximately 3,500 road safety certificates.

Mr Moran was convicted following a nine-day trial in the Brisbane District Court, and his accomplices were also imprisoned for their involvement in the scheme. Queensland Transport outlaid $665,000 to re-examine those vehicles for which false road safety certificates had been issued.

The prosecution followed a joint investigation by the CMC, Queensland Transport and the QPS. The CMC received very favourable feedback from Queensland Transport and the prosecutor involved in this case regarding its part in the joint investigation of this extensive and complex fraud.

For more information about the CMC’s work in 2006-07, read the annual report.